AI Boom vs. the Dot-Com Bubble

Key Differences in Business Models and Fundamentals

Setting the Stage

Honestly, this topic could fill an entire book and was a challenge to write for a short post. Today’s AI market isn’t a single story, it’s got many layers. You’ve got the AI hyperscalers and mega-cap giants, the semiconductor companies, and the large- to mid-cap software and digital apps building on top of it all.

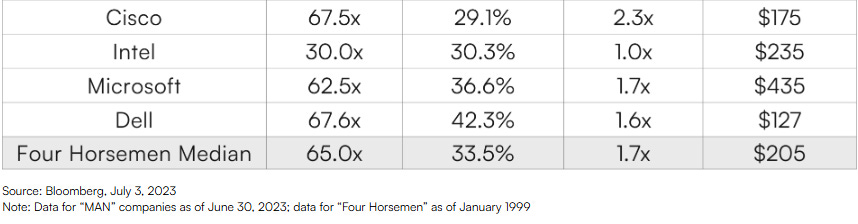

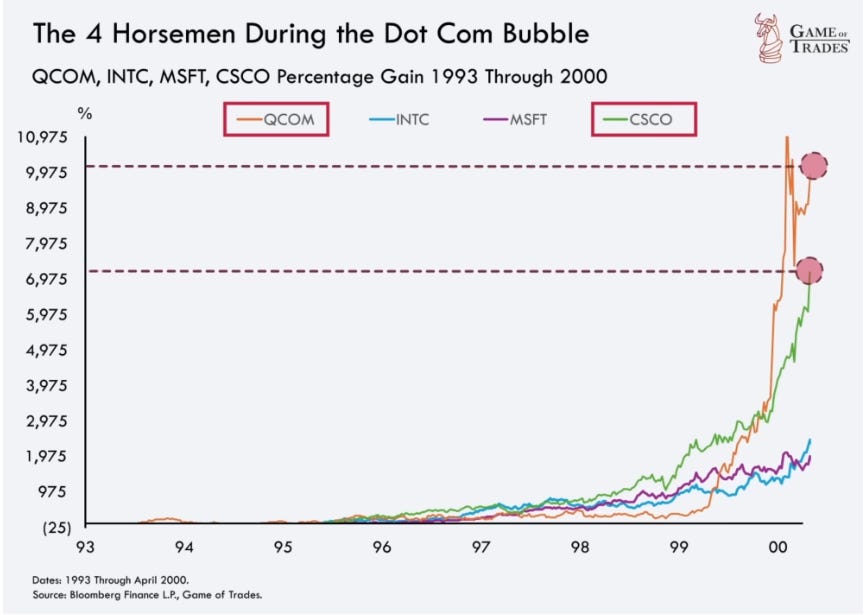

This complexity is why I chose not to simply compare valuations between today’s leaders and the “Four Horsemen” of 1999 for example. They were not always the largest weights in the Nasdaq, but at times drove more than half of the Nasdaq’s price movement.

Some analysts at the time also pointed to Qualcomm as a ‘horseman,’ given its crazy stock surge in 1999.

Why did I choose to focus more on SaaS (Software-as-a-Service) companies rather than the hyperscalers? Because when drawing comparisons to the dot-com bubble, I see stronger parallels in businesses like Figma or Palantir than in giants such as Nvidia or Microsoft.

It’s also worth noting that this post was written before Figma’s Q2 earnings report, scheduled for release after market close on Wednesday, Sept 3rd, 2025. This will be the company’s first earnings report since its IPO on July 31st, 2025.

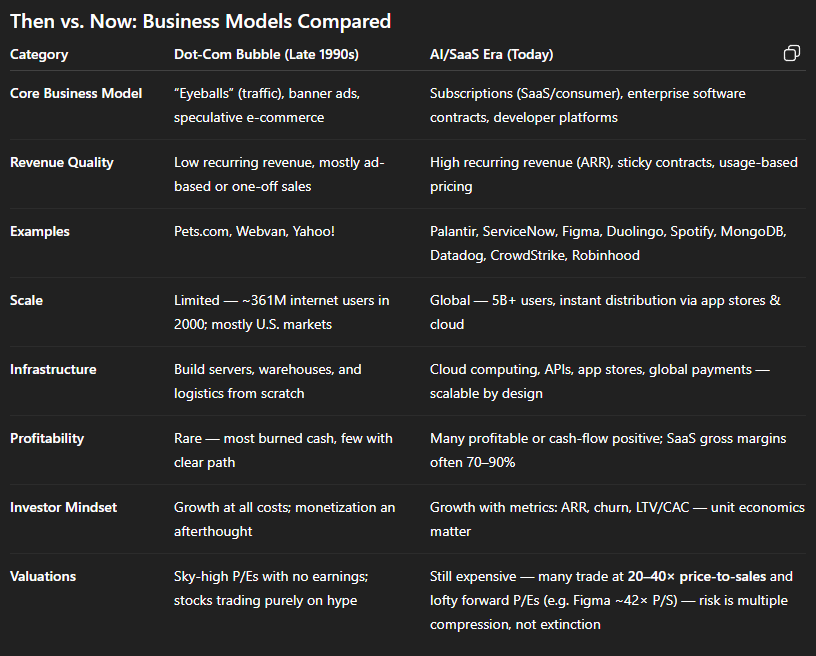

It’s a Different World Today

The AI stock market boom today is fundamentally different from the dot-com bubble of the late 90’s. Back then, dot-com companies were often valued on eyeballs, computer unit sales, estimate e-commerce sales and ad revenue. Today, modern tech companies thrive on disrupting entire industries, built on recurring revenues, and at massive scale through advertising and platform ecosystems.

Charts comparing the S&P’s forward P/E and Price-to-Sales levels to 2000 peaks are being shared relentlessly online. But the market structure today is very different from 25 years ago. Passive retirement flows from 401(k)s and target-date funds now provide a relentless bid under large-cap index weightings.

Today, the Magnificent 7 makes up nearly half of the Nasdaq-100 (45.7%), while the 10 largest companies in the S&P 500 account for about 40% of the index. Although these indexes are more concentrated today in a handful of mega-cap names, it’s also true that these companies are healthy, massively profitable, and still growing consistently.

During the dot-com bubble, most leading tech companies had razor-thin margins or no profits at all (except for some outliers like Microsoft). By contrast, today’s giants are operating with levels of profitability the market has never seen in tech.

While we see stretched valuations in AI themed stocks (Palantir being the best example), the tech sector today is largely driven by somewhat predictable, ongoing income. Additionally, these businesses can scale globally almost instantly thanks to the mature digital infrastructure of the internet and cloud computing, something that wasn’t possible during the dot-com era.

The ability to reach billions of users worldwide (both consumers and enterprises) gives today’s companies unprecedented room to scale. Combined with cloud services and global payment systems, they can grow faster and more profitable while keeping costs low, freeing them up to focus on innovation instead of building everything up from scratch.

We can use Figma as the most recent example, given its high-profile IPO this summer. The company serves more than 13 million users, including a large share of the Fortune 500 companies. Figma is already profitable. Its gross margins of 88-91% put it in elite SaaS territory, while its operating margins near 18%. Figma also continues to expand inside existing enterprise accounts, with a net dollar retention rate of 132%, meaning customers not only stick around but spend more each year.

Am I suggesting that Figma is a great buy at today’s valuations? Of course not. Even after its significant pullback, Figma still trades at 42x sales. And that’s exactly why we have to ask whether some of these valuations are starting to look as unrealistic as those from the dot-com era.

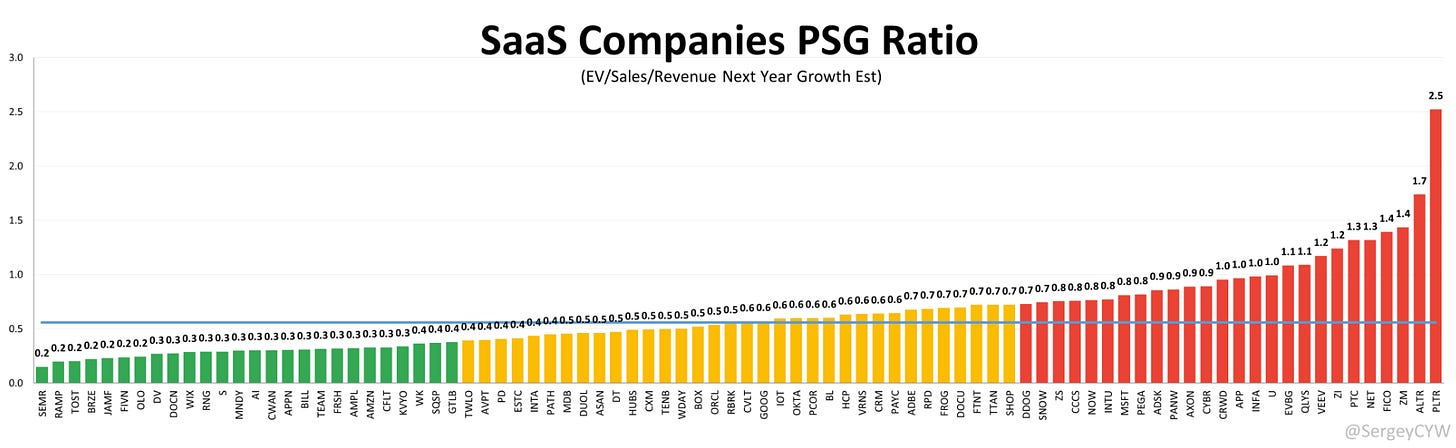

I’m also not suggesting you “shouldn’t” buy the stock either. Many prominent software investors use metrics like Price/Sales/Growth (PSG), which adjusts for a company’s growth rate and can justify higher multiples in fast-scaling businesses. Some software investors like

on Substack prefers an EV/Sales-to-Growth formula, which uses next year’s revenue growth estimate.

So let’s bring this back to investing and navigating today’s market:

It’s my opinion that another 80% wipeout across the Nasdaq, where companies vanish and it takes 16 years for the index to recover, is unlikely. A more realistic bear-case scenario is painful multiple contraction, similar to 2022 when the Nasdaq fell ~35% and many tech stocks were cut in half.

2022 was a classic growth slowdown, but most companies adopted and returned to expansion. The difference today is that tech companies are built on much stronger business models and operating in a global digital economy, unlike the year 2000.

Recurring Revenue Models

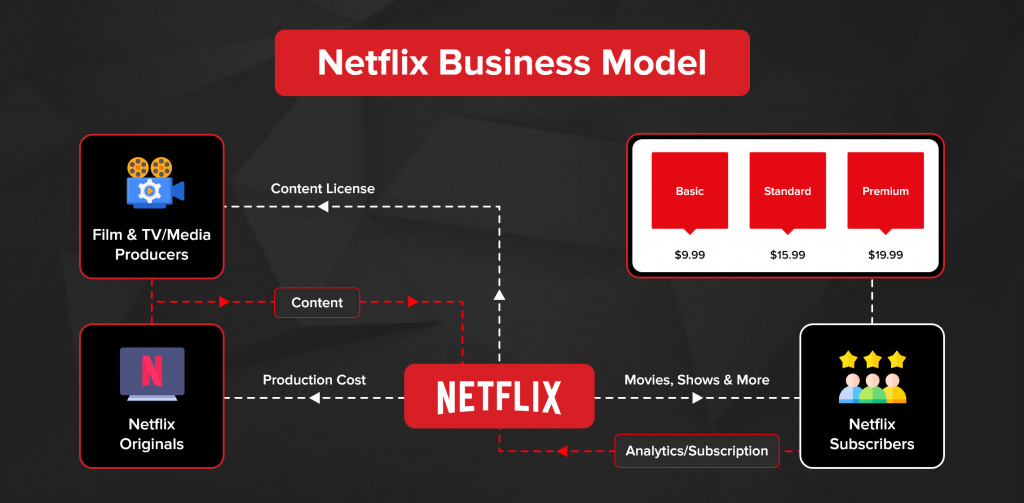

When we talk about subscription revenue power, the Costco membership model is often cited. But for the purpose of this post, let’s focus on digital subscription models, and there’s no better place to start than Netflix; the textbook case of how subscription economics can eventually tip-the-scale to profitability while disrupting an entire industry.

With it’s massive global reach, Netflix has become consistently cash-generative, layering subscriptions with ads and strategic price increases, all while maintaining strong consumer stickiness. That trajectory stets the stage for today’s AI-driven SaaS firms like Figma, Palantir, Datadog, Workday, ServiceNow, and many others. Their profitability is supported by deep enterprise adoption, high retention, high margins, and living in the digital era. The thesis is that with generative AI and global scale, today’s digital platforms can reach profitability and dominance even faster than Netflix did.

Venture investor Gavin Baker notes that company earnings today are far more resilient “given a more considerable amount of a company’s revenue is subscription-based.” whereas in 2000 that wasn’t the case. Another analysis at Digital One Agency observed, “Smart investors today understand (ARR) Annual Recurring Revenue, demand traction, not promises, and look at margins, not mascots. Companies today launch with clear monetization strategies instead of hoping to ‘figure out revenue later.’”

Global Scalability and Massive TAM

Another fundamental difference between today and the year 2000 is the scale and global reach tech companies can achieve thanks to a matured internet infrastructure and digital adoption. In 2000, the entire world had only about 361 million internet users, mostly in North America. Fast-forward to the year 2021, roughly 5 billion people (63% of the world’s population) are online.

This is simply a dynamic that dot-com darlings couldn’t exploit. As one commentary put it, the late 90s environment was limited, “the internet wasn’t ubiquitous, mobile wasn’t a thing…dial-up speeds throttled usability.” Whereas today, we have the perfect storm of cloud computing and storage, large sets of data for generative AI uses, smartphones, and broadband connectivity worldwide.

Let’s use the comparison of Duolingo and Spotify today, versus AOL or Yahoo. Duolingo, an education app, reported 130 million monthly users in Q1 2025. Spotify has grown to 696 million monthly active users as of Q2 2025. Meta reports 3.48 billion daily users as of June 2025. These kind of user bases, many paying monthly subscription fees, did not exist in 1999. AOL or Yahoo, had tens of millions users at best, and most weren’t generating recurring revenue.

Enterprise tech firms similarly benefit from online globalization, for example, Palantir counts major government and corporate customers in dozens of countries. ServiceNow has over 2,100 enterprise clients each paying $1million+ annually across the globe. Palo Alto Networks has roughly 70,000 clients across enterprises, governments and other institutions. These companies can keep expanding geographically and into new industries in ways dot-com startups couldn’t have dreamed of.

Although AppLovin is not a subscription business, it shows the sheer power of AI-driven digital advertising at scale, a reminder that global reach and massive TAM aren’t limited to SaaS alone.

Infrastructure Maturity and the Data Center

Back in the dot-com era, most startups had to buy and manage their own servers, or pay to house them in third-party data centers. Either way, it was capital-intensive, slow to scale, and often unstainable. Many firms spent more on infrastructure than they ever earned in revenue, one reason so many went out of business.

Today, tech businesses can rent out world-class cloud and GPU capacity from Amazon, Microsoft, Google, and Oracle by the hour, scaling up or down instantly. The cloud hyperscalers, the most profitable and cash-rich firms in history, are now the ones building out the physical data centers. Having dominated the digital transformation era, they can plow hundreds of billions of CapEx into AI infrastructure with the hope of not threatening their core businesses.

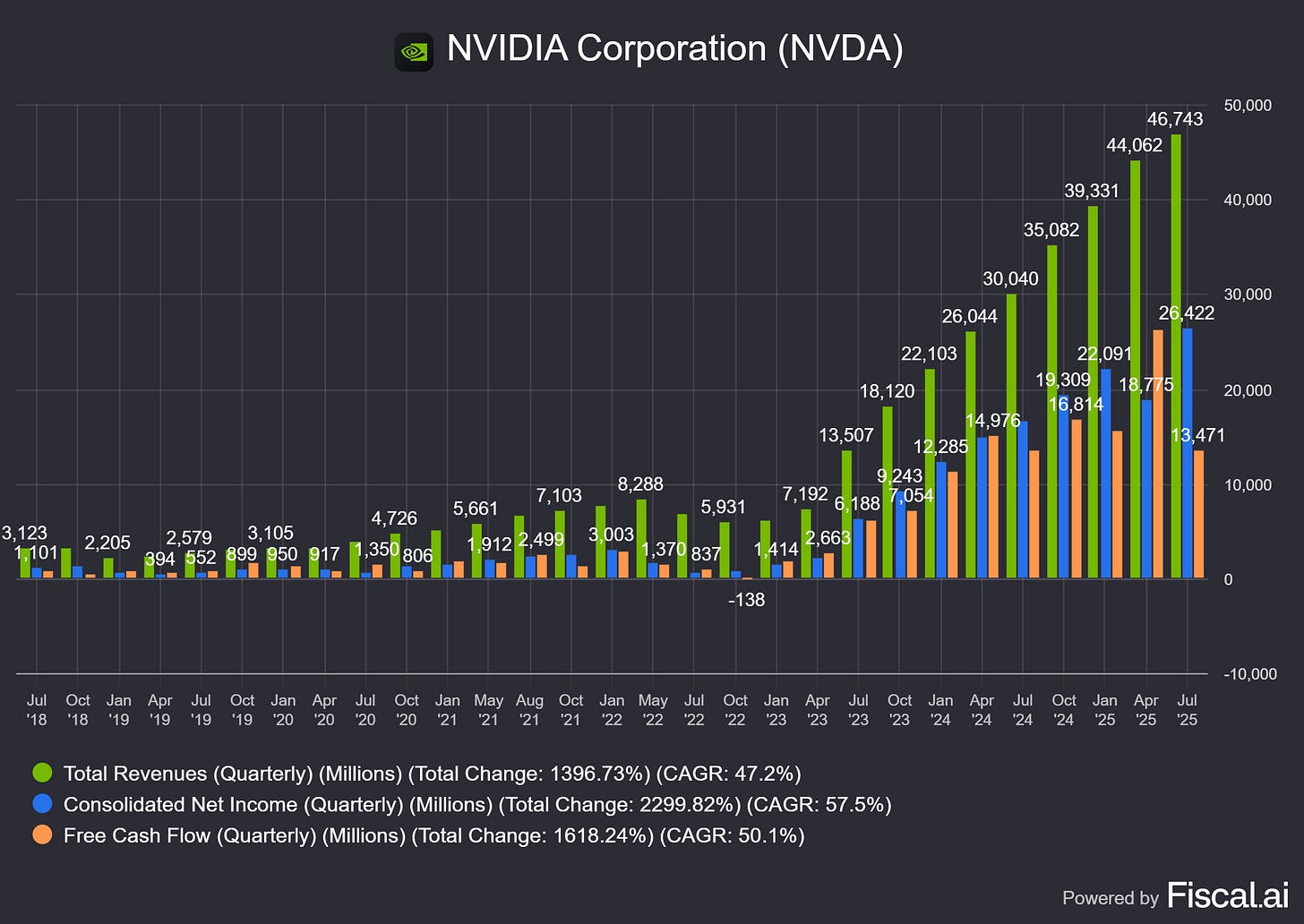

This is a huge aspect to the AI economy, and has to be mentioned in comparison to the 90’s. The hyperscalers’ massive CapEx have created a ‘boom within the AI boom.’ Their spending spree has unleashed a monster, but in this case a healthy one (see visual below).

Let’s not forget without GPUs, networking chips, and servers, today’s AI revolution wouldn’t be possible. Nvidia is the AI arms dealer that has made this boom far more durable than the internet buildout of 2000.

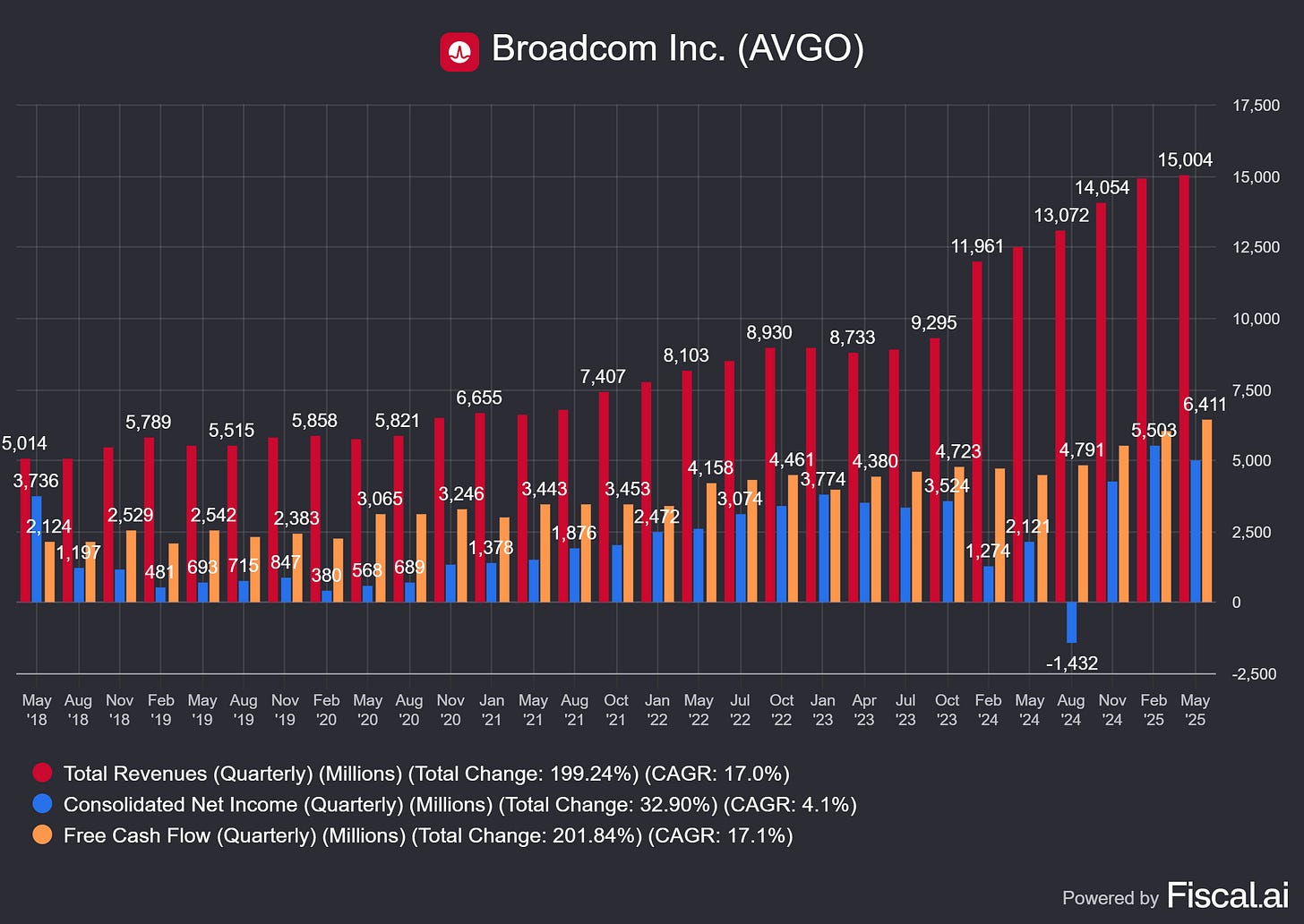

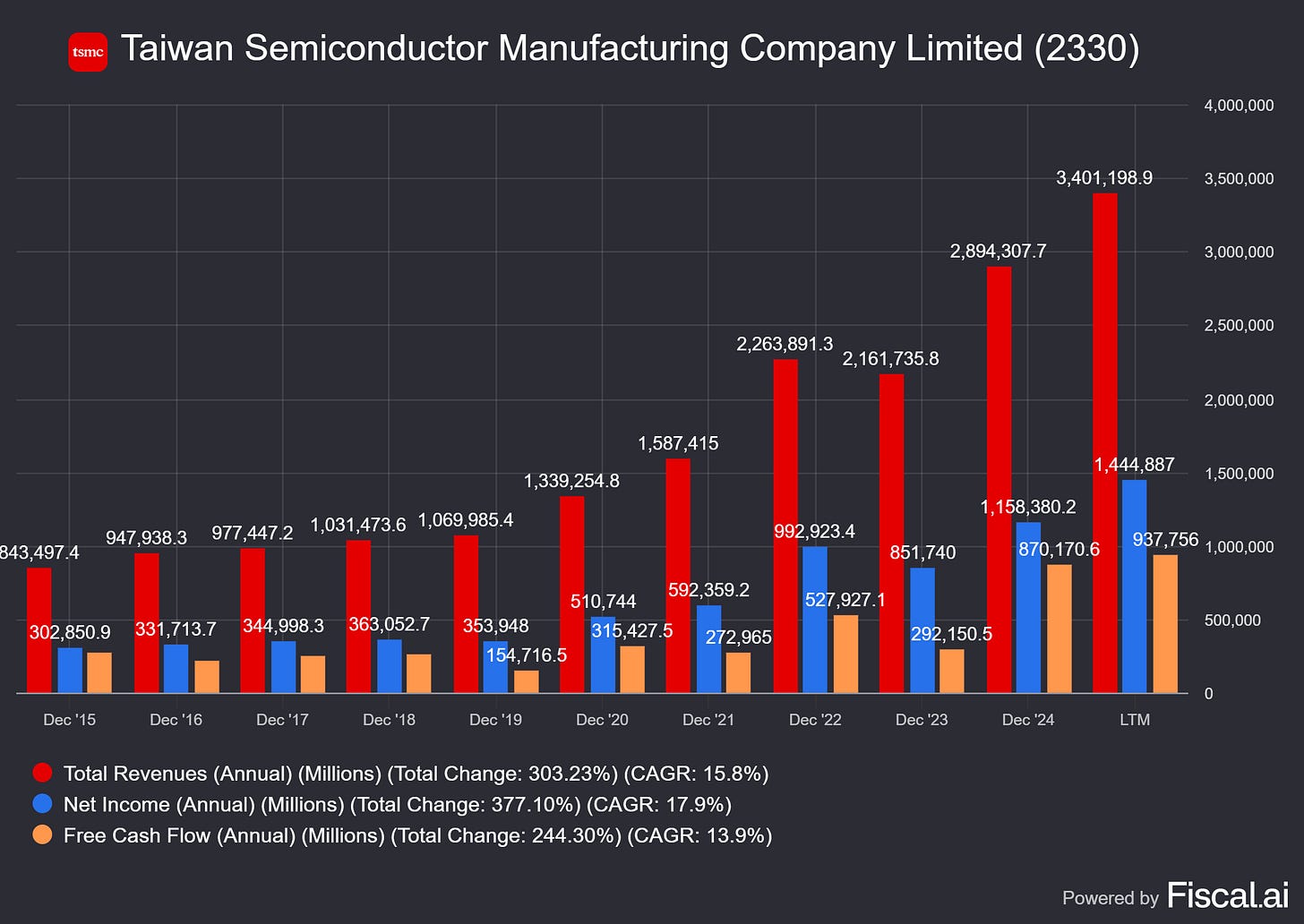

The AI buildout goes beyond just Nvidia. Broadcom is supplying everything from chips to networking to software. It would also be unfair not to mention Taiwan Semiconductor, the company that actually manufacturers the chips that make this rollout across data centers possible.

One Bear Case: Commoditization Risk

One of the risks with AI tech is that speed and innovation cuts both ways. The same tech that lets companies like Figma scale at record pace also lowers the barrier for challengers to enter. Competitors such as Framer are raising capital quickly and positioning themselves as alternatives, to both Figma and Squarespace. That highlights the danger of an industry where new entrants can “one-up” incumbents in a short cycle.

We’ve already seen how this dynamic plays out: Adobe, once untouchable in creative software, is now constantly compared against Figma’s more modern, collaborative AI design platform. If Adobe “could” be disrupted, so can today’s disruptors.

If every startup can spin up similar features on top of open-source models and cloud GPUs, then margins, pricing power, and customer loyalty could erode. We can already see this concern in large language models (LLMs): OpenAI’s ChatGPT may have been first to scale, but today it’s one of many, competing against Anthropic’s Claude, Perplexity, Grok, Meta’s LLaMA, and Google’s Gemini. To the end user, these models can start to feel interchangeable, which limits differentiation and pushes competition down to price.

Another recent example is Duolingo. Its stock recently sold off after reports suggested LLM’s could rival its ability to educate, followed by Google Translate launching its own learning tools. It’s a reminder that even with Duolingo’s success in integrating generative AI into its product, investors still have to ask: what kind of moat does it really have if giants like Google can replicate or outpace its features?

Personally, I’m not very worried about this bear case myself, but it’s worth raising because it highlights the difficulty of picking winners in fast-moving markets. If it were easy to spot the next dominant platform, every investor would do it. It’s important to look for real moats. These usually share common characteristics like: founder-led, great management, margin expansion, sticky products, strong retention, strong patents, and brands with great reputation.

Conclusion

In case anyone skipped my introduction, let me be clear: this is not an AI hype piece. And it’s certainly not a hype piece about Figma, Palantir, or any other expensive tech stock trading at stretched valuations today.

As I wrote up front, “It’s my opinion that another 80% wipeout across the Nasdaq—where companies vanish and it takes 16 years for the index to recover—is unlikely. A more realistic bear-case scenario is painful multiple contraction, similar to 2022 when the Nasdaq fell ~35% and many tech stocks were cut in half.”

To illustrate why today’s environment is different, I included a table below comparing business models from the dot-com era with those of today’s AI-driven SaaS companies.

It’s important to stay diversified and look at sectors beyond tech that may also benefit from AI, like Financials for example. Brent Schutte, CIO of Northwestern Mutual, recently pointed out on the Excess Returns podcast that while companies like Nvidia may be “laying the tracks” for AI, just as Cisco did for the internet, investors should remember what happened after 2000. The internet turned out to be very real, but the Nasdaq didn’t reclaim their highs for nearly 17 years.

Schutte also notes the MIT study that came out recently, showing that 95% of companies still haven’t figured out how to use generative AI to actually grow revenue, suggesting that the real winners may eventually be the firms that apply AI just to expand margins.

The MIT study may be out of context here, because my argument isn’t that every company is figuring out how to monetize AI today, it’s that a select group of mega-cap tech and leading SaaS firms are already showing both revenue growth and margin expansion from it.

Valuations are stretched in tech, but the underlying businesses are fundamentally stronger than what we saw in the dot-come era. As I’ve argued throughout this post, the case rests on three major themes: recurring revenue models, global scalability, and an infrastructure foundation that lowers risk and cost.

Thank you for reading, and please subscribe for more content on long-term investing.

References:

AI Boom vs. Dot‑Com Bubble: A Revolution or a Rerun?

Dot Com Bubble Versus Today - Bravos Research

The Magnificent 7: Who Kept the Most Profit Last Year?

Stop Comparing the AI Boom to the Dot-Com Bubble—This Is Nothing Alike

Is Figma Stock an Obvious Buy Right Now?

Is Generative AI a Bubble? Our Answer is No

2025 AI Tech Rally Vs. 1999 Dotcom Bubble: You Ain't Seen Nothing Yet

The AI Boom vs. the Dot-Com Bubble: Have We Seen This Movie Before?

Dissecting the AI boom through the dotcom lens

3 Reasons Why AI Enthusiasm Differs from the Dot-Com Bubble

5 Interesting Learnings From Figma at $900,000,000+ ARR. The B2B IPO of The Year?

Google Translate takes on Duolingo with new language learning tools

Disclaimer: This blog is for informational purposes only and does not constitute financial advice. All opinions are my own, and I am not a financial advisor. The information provided reflects my personal views and is intended to encourage discussion and thought among readers. Investments involve risk, including the loss of principal, and past performance is not indicative of future results. Always conduct your own research or consult with a qualified professional before making any financial decisions.

Really thoughtful comparison — I like how you don’t just say “this is exactly the same” but dig into both similarities and differences. The scale of investment and infrastructure today is huge, but there’s also more real-revenue coming from big AI players. That said, the risk of overhype in smaller startups feels very real. Great breakdown.

Regards

Preeti

Broker at https://youandhouseproperties.com

Great post! 👍